Republished from the original source: JSTOR

Take a look back at how others have survived—and thought about—the high heat of summer.

In an episode of The Twilight Zone called “The Midnight Sun,” first aired in November 1961, the apocalyptic scenario of an Earth drawing nearer to the Sun is symbolized by a thermometer shattering at…130°F. On July 5, 2024, Palm Springs, California, recorded 124°F, and the following day, Death Valley hit 128°F amid a widespread heat wave that shattered temperature records across the American West.

Benchmarks have shifted. In 1961, the level of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere was 318 parts per million by volume (ppmv). CO2 is a greenhouse gas that acts as atmospheric insulation, preventing heat from escaping into space. By 2023, CO2 levels had risen to 421 ppmv and continue to increase, exacerbated by the paradoxical practice of burning fossil fuels to stay cool in a warming world. We find ourselves in a global greenhouse, where attempts to cool down contribute to the very problem—more CO2 emissions—from which we are trying to escape (CO2 details).

Humans have long employed strategies to combat heat, particularly in tropical and desert regions. Their methods—avoiding the midday sun, living underground, and covering up completely—were often dismissed by those from temperate climates, sometimes with a touch of racism. However, as temperatures rise globally, more regions are adopting these time-tested approaches.

(picture inserted here, do not change the place)

What would life be like without air conditioning? A glimpse of this is offered by this piece from 1858 titled “Hints for Keeping Cool,” which recommends eating “fruits, vegetables, and farinaceous food, and the lighter kinds of meat.” At that time, the atmospheric CO2 level was 286 ppmv. Just seven years earlier, in 1851, Dr. John Gorrie patented the first ice-making machine in an effort to cool his malaria and yellow fever patients in Florida (CO2 was 285 ppmv then).

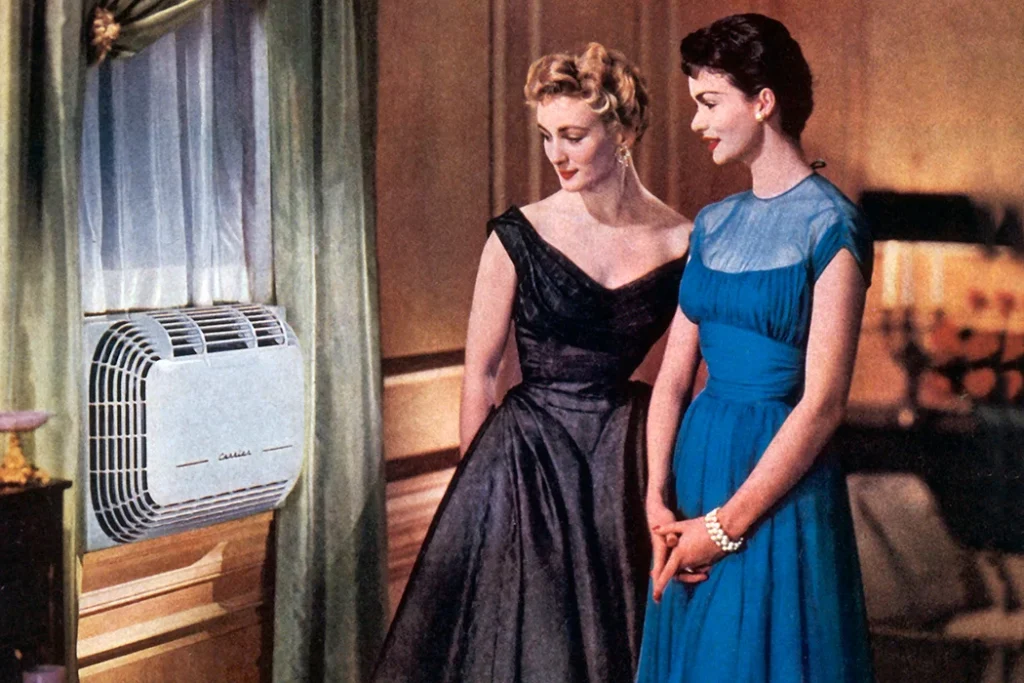

The first modern electrical air conditioning system was developed in 1902 (297 ppmv) by Willis Carrier, who invented it to cool and dehumidify the Sackett-Wilhelms Lithographic & Publishing Company in Brooklyn, New York. The company needed to protect its paper supplies from warping due to humidity. Carrier’s invention remains significant today.

By 1961, just over a century later, The Science News-Letter published an article titled “Keeping Cool in Summer Heat” (318 ppmv), which emphasized the need for knowledge about coping with heat, offering tips for those without air conditioning.

Getty

“If you suffer from heat frustration when the mercury hits the 90’s, a little scientific knowledge of summer heat can help your body temperature and state of mind remain well within the comfort zone,” the editors advised.

These tips were invaluable before air conditioning became ubiquitous in cars, theaters, restaurants, office buildings, and homes. Post-World War II growth in the Sun Belt—from Southern California to North Carolina—was largely fueled by air conditioning.

Raymond Arsenault’s exploration of how air conditioning reshaped the South includes a quote from a Floridian in 1982 (341 ppmv), who said:

“I hate air conditioning. It’s a damnfool invention of the Yankees. If they don’t like it hot, they can move back up North where they belong.”

Despite some resistance, most people, both in the South and elsewhere, embraced air conditioning enthusiastically. Historians have been cautious in attributing too much to air conditioning’s impact on the South, wary of reviving outdated notions of climate determinism, which once blamed the region’s climate for everything from the Southern drawl to plantation slavery. However, by the mid-20th century (1950: 311 ppmv), as the civil rights era’s “long hot summers” gave way to the “New South,” air conditioning had become a fixture of indoor life.

In “The Midnight Sun,” the protagonist wakes from a fevered nightmare to a freezing, dark night. She’s so relieved by the cold that her neighbor can’t bear to reveal the truth: the Earth is actually drifting away from the Sun and freezing.

We are skilled at imagining climate apocalypses. Robert Frost, in his 1920 poem “Fire and Ice,” touched on the potential ends of the world. While we discuss climate changes and predictions, the future of our warming planet remains uncertain.

In contemplating historical strategies and innovations, we may find ways to better address the challenges of a climate-changed future.

Leave a Reply