A science philosopher outlines how the industry can explore other planets without exploiting them.

Over the past decade, the commercial space industry has expanded rapidly, with rival nations vying for strategic military and economic advantages beyond Earth. Both public and private sectors are eager to mine the Moon, while an increasing cloud of space debris continues to pollute low Earth orbit.

In a 2023 white paper, a group of concerned astronomers cautioned against replicating Earthly “colonial practices” in outer space. But what’s the harm in colonizing space if it’s seemingly empty to begin with?

As a philosopher of science and religion, I have been examining the space industry for several years. As government agencies and private companies set their sights on the stars, I have observed many of the same forces that fueled European Christian imperialism between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries resurfacing in modern, high-speed, high-tech ways.

These colonial practices can include land appropriation, exploitation of natural resources, and the destruction of landscapes, all justified by ideals like destiny, civilization, and the salvation of humanity.

Many leaders in the space industry, including Mars Society President Robert Zubrin, contend that while European-style colonialism may have had negative impacts on Earth, it remains the only viable path forward in space. Zubrin cautions that any efforts to slow down or regulate the space industry could render the Martian frontier unreachable, confining humanity to an increasingly stagnant and declining Earth.

Zubrin dismisses concerns about colonialism in space by arguing that, unlike Earth, outer space is empty. Why, he asks, should we worry about the rights of rocks and some hypothetical microbes? However, not everyone shares his view that space is devoid of significance. Concerned astronomers argue that abandoning the colonial mindset could benefit both those within the industry and those outside it.

Is Space Truly Empty?

The people of Bawaka Country in northern Australia have shared with the space industry that their ancestors, residing in the galaxy, play a guiding role in human life, and that this sacred relationship is increasingly jeopardized by the expansion of large satellite networks in orbit.

Similarly, Inuit elders believe their ancestors reside on celestial bodies. Navajo leaders have requested that NASA refrain from landing human remains on the Moon. Kanaka elders have urged that no further telescopes be constructed on Mauna Kea, a site that Native Hawaiians regard as ancestral and sacred.

These Indigenous perspectives sharply contrast with the space industry’s common view that space is empty and lifeless. The key to bridging these differing viewpoints lies in finding common ground—not in shared beliefs or worldviews, but in actions. Secular space enthusiasts do not need to accept that space is inhabited, alive, or sacred to act with the care and respect that Indigenous communities are asking from the industry.

Environmental Considerations

The emerging field of space ecology explores the interactions between human-made objects and natural environments within Earth’s orbit, on the Moon, and on other planets. This discipline aims to show that orbits and planetary bodies are finely balanced systems. Without proper regulation, commercial space activities could make orbits unusable and disrupt the Moon’s delicate, vacuum-like atmosphere.

Moreover, light reflecting off tumbling space debris—such as defunct satellites, spacecraft fragments, cellphones, nuts, bolts, and shards of metal and glass—can obstruct astronomers’ ability to observe, photograph, and navigate using the stars.

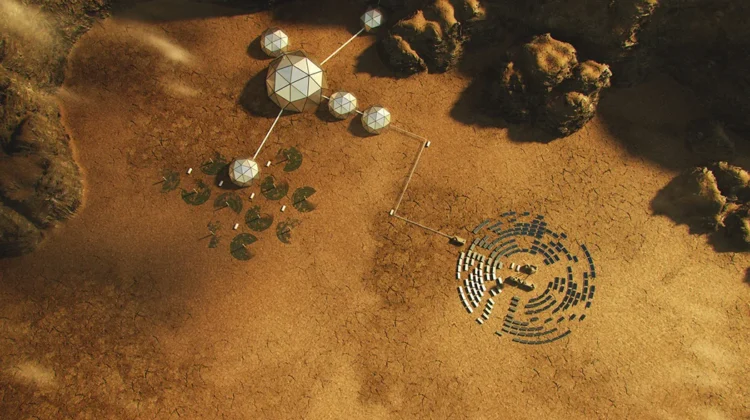

The Moon, Mars, and asteroids provide scientists with crucial insights into the formation of planets and the solar system, the conditions required for life, and what planets may look like in the future. However, if the space industry engages in blasting, mining, or even nuking these planetary bodies—as suggested by SpaceX CEO Elon Musk—scientists risk losing access to this valuable knowledge.

The commercial space industry has already caused considerable environmental damage on and around Earth. SpaceX’s frequent rocket tests and launches have severely impacted the wetlands of Boca Chica, Texas. In April 2023, a SpaceX Starship explosion damaged approximately 385 acres of land, waterways, and local wildlife, including turtles and birds, in addition to affecting cars, homes, and human health.

The increasing number of private and public rocket launches deposits kerosene, carbon, and sulfur into the upper atmosphere, where these pollutants linger much longer than they do in the stratosphere. Research indicates that the accumulation of these substances could dramatically accelerate climate change, with one estimate suggesting that rocket emissions heat the atmosphere 500 times faster than aviation emissions.

Even if Musk never reaches Mars, SpaceX and numerous competitors are filling low Earth orbit with satellites, creating traffic that threatens astronauts’ safety and risks rendering these orbits unusable.

Impact on Humanity

Many leaders in the space industry view space as the new New World or the final frontier. However, the early modern economies driven by sugar, tobacco, and gold generated immense profits for Europe and the early United States through practices like enslavement and indentured servitude.

As the space industry expands, its leaders must carefully consider the nature of labor arrangements as workers are sent to operate space hotels, build underground bunkers, and mine asteroids. Space workers will depend on their employers not just for wages and healthcare, but also for essential resources like food, water, air, and safe transportation back to Earth.

In 1967, several nations, including the US, UK, and USSR, signed the Outer Space Treaty, which among other provisions, declared that no nation could claim ownership of any part of a planetary body.

Signed in the aftermath of two world wars, the Outer Space Treaty was shaped by the conflicts that ravaged Europe in the twentieth century. Recognizing that colonialism on Earth had culminated in devastating global wars, the treaty signatories essentially agreed, “Let’s not fight over territory and resources again—let’s handle outer space differently.”

Today, the Outer Space Treaty is outdated and nearly impossible to enforce, but any future legislation would benefit from preserving the anticolonial ethos that inspired the original agreement.

From a policy standpoint, the question of whether space is inhabited or whether rocks have rights is irrelevant. Preventing colonialism in outer space doesn’t hinge on the space industry agreeing on these metaphysical issues.

Rather, it requires a consensus among industry participants and beyond on a common set of standards for caring for planets and their orbits—whether their motivations are scientific, environmental, humanistic, or religious.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Leave a Reply